By Robert Orttung and Fredo Arias-King

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the peaceful disintegration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, after a string of events that would have seemed unimaginable just a few years before.

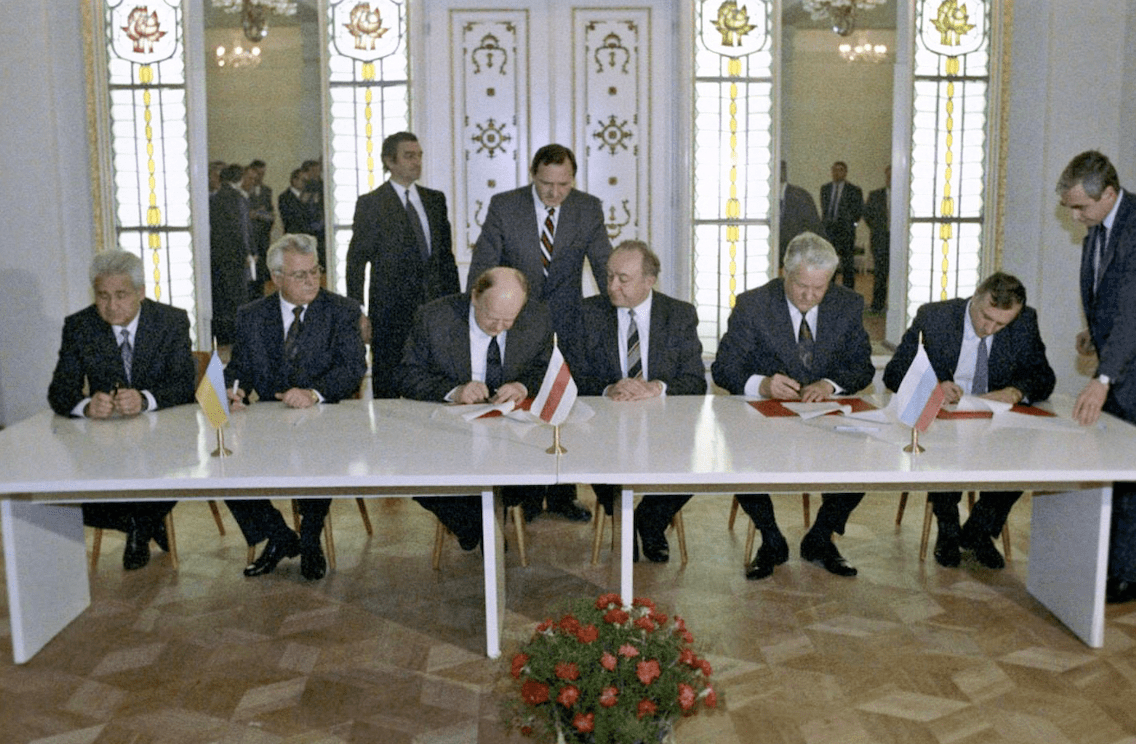

To this day, observers still disagree on the main causal factors. We once drew up a list of 40 potential causes – structural factors, calamities, external pressures, and personalities – and their timing and relative importance remain contentious among historians and political scientists. Russians embittered by imperial disintegration usually blame the meeting which produced the Belavezha Accords, a document that replaced the USSR with the Commonwealth of Independent States.

When the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, the three Soviet Slavic republics, met at a hunting lodge in western Belarus on December 8, 1991,and unexpectedly agreed to dissolve the USSR, it took only two weeks for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to acknowledge the inevitable and resign gracefully. The red flags were lowered from atop the Kremlin for the last time, replaced by the Russian tricolor. Twelve new countries gained global recognition, the three Baltic republics having seceded the previous August.

The structural factors were certainly there: The Soviet constitution since Stalin’s times loftily declared that any republic that wished to leave the USSR could do so. The Communist ideology and institutions that had founded the USSR in 1917-1924 had been discredited, especially following the failed August 1991 coup. The USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (the larger Soviet parliament, elected in March 1989) voted to dissolve itself just days after the coup’s collapse. Most Soviet republics had even stopped financing the Soviet government even before the coup, forcing it to cover its costs with massive monetary emissions, deepening its bankruptcy and the dire economic situation.

Public opinion and politics also called for dissolution. Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk walked into the Belavezha negotiations emboldened by a referendum where over 70% of Ukrainians voted for independence, even in the mostly Russian-speaking areas. Russian President Boris Yeltsin had been dithering on the new Union Treaty convinced that Russia would benefit from leaving as well, making him the new president. Belarusian leader Stanislau Shushkevich, a scientist who gained notoriety by denouncing the lies emanating from Moscow after the Chernobyl explosion in 1986, gladly added his vote.

After Belavezha, the other Soviet republics’ leaders called for a new, broadened summit and signed the Alma-Ata Accords, formalizing their declarations of independence. Crucially, the parliaments of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus overwhelmingly voted to reaffirm the Belavezha Accords, even the Communist factions. (“Today, we vote for independence!” the head of the Ukrainian communists famously ordered his deputies that day.) The military top brass crucially stepped aside, its main general, defense minister Yevgeny Shaposhnikov declaring that if the legitimate parliaments of the sovereign republics voted to secede, there was nothing the military could do. We learned from hosting Gennady Burbulis, a co-signer of Belavezha as Russia’s first deputy prime minister, that there was not a single military commander who opposed the Belavezha Accords. In fact, both Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Gorbachev met separately with the same group of top military commanders to pitch their respective projects, and they backed Yeltsin’s (admittedly, he offered to raise their salaries).

While critics blame these leaders for dissolving the USSR, in fact the real culprit (as they themselves remind us often in their defense) was the abortive coup against Gorbachev and his Soviet democracy project that previous August. After years of crisis, the Soviet center was about do devolve powers to its constituent republics. The hardline plotters, representing neither Communist ideology nor the Communist Party itself (which was rudderless and in disarray) but the crumbling Soviet institutions and a mentality that viewed a new constitution as a threat, made a clumsy move to seize power, arresting Gorbachev at his summer compound in Crimea for three harrowing days while the recently elected Russian president, Yeltsin, and thousands of Russian and Soviet citizens across the USSR’s 11 time zones, rallied against the coup plotters.

When Gorbachev returned to Moscow after being rescued by a delegation led by Yeltsin’s vice president Aleksandr Rutskoi, his powers were disintegrating by the day. He continued to fight for his reformed Union project through persuasion and negotiation until the very end, warning of dire consequences if the republics did not stay together. But as numerous papers (and Bill Taubman’s new biography) vividly attest, only his most loyal lieutenants such as Aleksandr Yakovlev, Anatoly Chernyaev, Georgy Shakhnazarov, and Pavel Palazhchenko, were sticking around in the Kremlin—most others flocked instead to Yeltsin’s White House those frosty December days. Gorbachev later declared that his main achievements were to bring freedoms to his people, and then stepping aside.

One wonders if that coup had not happened, what would have become of the new Union of Sovereign States, the USSR minus about five small republics but keeping a semblance of a common political and economic space with even more freedoms than what Gorbachev had managed, against all odds, to achieve for his people in his almost seven years in power.

Gorbachev’s supporters argue that someone like Belarus dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka would probably not have risen to power if Gorbachev’s new Union had survived. But what if it had been the opposite, and the new USSR would not have been governed by Gorbachev or a fellow reformer? We agree with the analysts who argue these Soviet republics were far too disparate (culturally, developmentally, even geographically) to coexist, and the richer and larger republics such as Russia and Ukraine would probably have reduced their subsidies and essentially jettisoned the poorer ones eventually anyway. The Soviet dissolution could have come later and not so peacefully as it did.

Because Russia experienced only a partial transformation, several groups within the country never truly accepted an independent Ukraine and Belarus, the latter for the first time in 300 years. For example, Vladimir Putin after the seizing of Crimea and fostering insurgency in part of eastern Ukraine in 2014, even said that Ukraine had not seceded legally from the USSR. He continues to question Ukraine’s independence.

Both Russia and Belarus remain unstable today. Knowing that history is full of surpises, we can even speculate that if we witness a sharp delegitimization and sudden collapse of the Putin and Lukashenka regimes, both Gorbachev and Shushkevich could find themselves as provisional presidents of their respective countries while new elections are organized.

Such an outcome might make it possible for Gorbachev and his surviving allies to achieve some of the things that he sought during his years in power: Representative government, freedom of the press and assembly, disarmament and denuclearization, legality and protection of civil liberties, de-imperialization, economic development, and good relations with the outside world.

_________________________________________________________________________

Robert Orttung is a research professor of international affairs at George Washington University and editor of the peer-reviewed journal Demokratizatsiya. Fredo Arias-King founded Demokratizatsiya in 1992.